(6/10 stars)

(6/10 stars)

“There’s no room for idealism in the next twenty-four hours. This time the truth has got to be stage-managed—I’m going to set the stage and act for all I’m worth. There won’t be any room for ideals or hopes or fears, or anything but sheer showmanship.”

At four past four, Clare Charters phones neighboring Barslade Manor in a panic. She tells famed detective James Segrove that a burglar has just shot her husband.

At twenty-four past four, Segrove and his physician friend arrive at Clare’s home, to the sound of a gunshot within. They discover that her husband Herbert Dempster has, indeed been shot—but the bullet could not have been fired more than a minute ago. Clare Charters is England’s greatest living actress. Segrove must find out whether Clare is the grieving widow she appears to be, or whether she’s a cold-blooded murderess performing the role of a lifetime.

Reading Four Past Four in a 1945 Detective Book Club volume, it comes across as an oddity, an old-school puzzle mystery adrift in the postwar era of noir and psychological suspense. It turns out there’s a reason for that—Four Past Four is the real thing, a 1925 novel by Roy Vickers that was not published in the United States until twenty years later. It’s an entertaining golden-age mystery that is deeply concerned with timetables and firearms, but also with those more subjective elements that bedevil an investigation and can be more convincing than all the hard evidence in the world.

Everything indicates that Clare Charters is lying about what happened when her husband Herbert was killed. Herbert Dempster was known to be “a little beast,” jealous of his wife’s success. “If an ordinary American were to speak to his wife in presence of guests as Mr. Dempster spoke to his wife when we were at their place the other day,” says Segrove’s sidekick Dr. Birbeck, “those guests would walk out of his house and never enter it again.” In addition to the medical evidence of Herbert’s freshly inflicted wound, which casts doubt on Clare’s timeline, Segrove proves that at least two men were present at the crime scene, not the one she describes. Her story would require two gunshots, the one at 4:04 and the one Segrove and Birbeck heard at 4:24, but the murder weapon was fired only once.

Everything indicates that Clare Charters is lying about what happened when her husband Herbert was killed. Herbert Dempster was known to be “a little beast,” jealous of his wife’s success. “If an ordinary American were to speak to his wife in presence of guests as Mr. Dempster spoke to his wife when we were at their place the other day,” says Segrove’s sidekick Dr. Birbeck, “those guests would walk out of his house and never enter it again.” In addition to the medical evidence of Herbert’s freshly inflicted wound, which casts doubt on Clare’s timeline, Segrove proves that at least two men were present at the crime scene, not the one she describes. Her story would require two gunshots, the one at 4:04 and the one Segrove and Birbeck heard at 4:24, but the murder weapon was fired only once.

At the same time, Segrove can’t shake his feeling that Clare is innocent, even as he remains equally convinced that she’s using her dramatic abilities to affect the investigation. “She’s far cleverer than I thought,” he tells himself at the inquest. “She is playing the sorrow that is too deep for tears or mourning—and she’s getting across with everybody in this room.” He is left unsure of whether she’s a manipulator, or whether he’s simply talked himself into believing that.

His heart thumped and there came a sinking sensation in the middle of him.

Stage-fright! That was it. Obviously she was not sending for him for the purpose of telling him the truth. She was going to act. And unless he intended to tell her the truth, he would have to act too. Panic gripped him. He saw himself playing the part of himself—the Unsuspicious Detective talking to the Woman with a Secret.

Segrove puts his faith in physical evidence. It points toward Clare’s involvement. But what can a detective do when all of his instincts are in direct opposition to the evidence?

This lends an unexpected emotional element to the story, as an otherwise rather dry collection of facts insist on leading down a path that the investigator would rather not travel. Yet Segrove regards himself as a professional with a reputation to maintain. It’s all very well for Birbeck to insist that a woman as beautiful and sensitive as Clare cannot be guilty. This is typical detective-story nonsense that irritates Segrove as much as it does the reader. Segrove holds himself to a higher, more objective, standard even as he rather despises himself for it, as when he prepares to question his weekend host Lord Robert Leeford.

Segrove shook hands. As he did so, there swept over him a sudden wave of disgust. He had met Leeford as an undergraduate at Oxford and in spite of a vast difference of temperament had rather liked him. They had kept in touch intermittently ever since. And now, he supposed, they were going to lie to each other and fence and cheat. At that moment he hated himself more than Leeford—for he was going to try and trap the man whose bread he had broken.

It is these little human moments that gum up the investigation and the murder, gestures of love, honor, or loyalty that make no logical sense in the midst of crime, but which happen nonetheless because feelings are the one thing that can’t be planned for. There are bits of humor as well; when Segrove hunts down a ham actor at a run-down provincial theater, the man is performing “the throbbing human drama” Hounded Down, based on one of Vickers’ own titles.

What emerges from all of this is a fiendishly complex crime plot with so many detailed and seemingly contradictory clues that even the most careful reader will be challenged. Segrove identifies “the Seven Absurdities” that must be accounted for in solving the crime. He cannot explain all of them until he allows for the absurdities of human emotion. After a slow start, Four Past Four develops into an enjoyable detective story that keeps an amazing number of balls in the air before bringing them all in for a satisfying conclusion.

Second Opinion

Saturday Review, October 6, 1945

Capably handled tale with well distributed red-herrings, amiable characters, and not-unforeseen ending with neat twist.

Availability

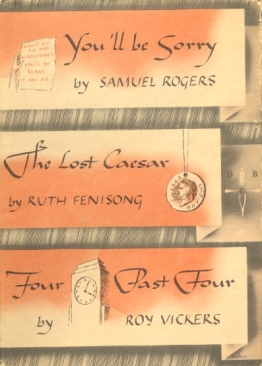

Four Past Four is out of print, and most easily available in the Detective Book Club edition with You’ll Be Sorry! by Samuel Rogers and The Lost Caesar by Ruth Fenisong.

I never realised Vickers was writing this early. Probably because I only ever tried his short story collection Department of Dead Ends, which I think was a bit later. Didn’t hugely enjoy the collection, but perhaps his longer work might be worth investigating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I love Department of Dead Ends, but this does have a very different feel than those later stories, being a more traditional detective story with a less ironic tone. The other novels of his that I have are all from later in the 1950s, so I wonder how those will compare.

LikeLike

Trivia time! Vickers started writing using the pen name “David Durham” and wrote one of the rarest of mystery books The Exploits of Fidelity Dove, a collection of short stories about a female thief. I still haven’t found a copy I could afford. There are only three copies of the 1st edition for sale and they are all priced between US$1200 and US$2500! I think I’ve read only a single Fidelity Dove story in an “ancient” anthology decades ago. Probably something Ellery Queen put together because Fred Dannay owned a reprint edition of the book in his vast library of detective fiction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Should have known you’d have the scoop on Vickers! Fidelity Dove does sound interesting–too bad it’s so rare.

LikeLike

Vicker’s The Exploits of Fidelity Dove is now available in ebook for those interested. https://www.rohpress.com/exploits_of_fidelity_dove.html

LikeLike