(10/10 stars)

(10/10 stars)

“To solve the puzzle of her death, you must first resolve the mystery of Laura’s life. This is no simple task. She had no secret fortune, no hidden rubies. But I warn you, McPherson, the activities of crooks and racketeers will seem simple in comparison with the motives of a modern woman.”

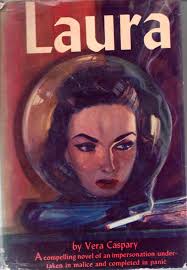

Laura Hunt was smart, beautiful, and successful. It’s easy to see how Mark McPherson fell in love with her. There’s only one obstacle to their relationship. Laura is dead, and Mark is the detective assigned to investigate her murder.

At least, that’s the summary of Laura that’s usually put forth, influenced by the excellent 1944 film adaptation. But that’s not Vera Caspary’s Laura, it’s Waldo Lydecker’s. The victim’s best friend Waldo, “the heavyweight Noël Coward,” is only one of the narrators of the novel. We also hear from Mark and (in flashback) Laura herself. Each character adds a slightly different perspective. Initially we accept Waldo as an authoritative narrator, believing him honest because he is willing to be cruel. By the time his narrative resumes at the end of the story, we begin to see how sadly mistaken he has been, about Laura and about himself.

Everyone agrees on the basic facts. Laura was supposed to spend the week before  her wedding at her country house in Connecticut. Before leaving, she planned to have dinner with Waldo, as she did every Friday night. But she never showed up for dinner and she never left for Connecticut. She stayed at home instead. Someone rang the doorbell. When she opened the door, they shot her in the face.

her wedding at her country house in Connecticut. Before leaving, she planned to have dinner with Waldo, as she did every Friday night. But she never showed up for dinner and she never left for Connecticut. She stayed at home instead. Someone rang the doorbell. When she opened the door, they shot her in the face.

Mark searches for answers among the Park Avenue parasites who make up Laura’s world. Waldo is a famous newspaper columnist who “discovered” Laura when she convinced him to endorse a line of pens for her advertising agency. Waldo introduced her to high society, considering her his “heroine…my greatest creation.” An avid collector, Waldo once smashed a vase he coveted but could not own. Might he have done the same to Laura? Her fiancé Shelby Carpenter is an impoverished southern gentleman. Laura picked him up, found him a job at her firm, and lent him money. She even made him the beneficiary of her life insurance. Susan Treadwell, Laura’s aunt, “once sang in musical comedy. Then she became a widow. The period between—the hyphen of marriage—is best forgotten.” The coquettish Susan doesn’t cry at her niece’s funeral, but she takes to her bed when she thinks Shelby has gone away.

Her friends all swear that Laura was the kindest person they ever met, generous to a fault. Yet none of them seem to mourn her very much. Even Waldo, who remains obsessed with Laura, doesn’t miss her as a person. He’s content to talk about her with Mark, endlessly turning her over in his mind like one of his objets d’art. Waldo ridicules Mark for his growing interest in Laura. “’Have you ever analyzed that particular form of romanticism which burgeons on the dead, the lost, the doomed? […] A most convenient leitmotif for the thriftiness of their passion toward living females.” But Mark seems willing enough to appreciate a living female when one comes his way. It’s Waldo who prefers the Laura of his memory, the Laura who wouldn’t tell him lies or skip their dinner dates.

Mark dislikes these shallow people and they look down on him in return. “He ought to be hardboiled,” Aunt Susan complains. “You’d expect him to be tougher. I don’t like him trying to act like a gentleman.” In fact, Mark is tough, having fought his way up from a working-class background to a high-level job. Although “a doll in Washington Heights got a fox fur out of him once,” he has thus far avoided marriage because he values his career and independence.

This sounds an awful lot like the ambitious self-made woman Laura Hunt, for whom freedom “meant owning myself, possessing all my silly and useless routines, being the sole mistress of my habits.” She’s put off her wedding for two years because she cannot see a way of keeping that freedom after marriage.

This sounds an awful lot like the ambitious self-made woman Laura Hunt, for whom freedom “meant owning myself, possessing all my silly and useless routines, being the sole mistress of my habits.” She’s put off her wedding for two years because she cannot see a way of keeping that freedom after marriage.

When Laura finally gets to tell her own story, she is feeling “desperate” at being unable to navigate the contradictory society she lives in. Laura wants a career and independence; she is to some degree living a man’s life, working and living just as she pleases. However, the world considers her a failure as a woman unless she marries, which would result in the loss of what she values most. She longs to fall in love but fears losing her identity in the process:

I thought of my mother and how she had talked of a girl’s giving herself too easily. Never give yourself, Laura, she’d say, never give yourself to a man. I must have been very young when she first said it to me, for the phrase had become deeply part of my nature, like rhymes and songs I heard when I was too small to fasten my own buttons. That is why I have given so much of everything else; myself I have always withheld. A woman may yield without giving […]

I was ashamed; I kept thinking of my own life that had seemed so honest; I hid my face from daylight; I thought of the way we proud moderns have twisted and perverted love, making arguments for this and that substitute, just as I make arguments for Jix and Lady Lilith when I write advertisements.

In the days leading up to the murder, Laura comes to a crisis point where she must finally decide what she really wants—first and foremost whether she should marry “a thirty-two-year-old baby.” Notably, she spends her last day at work training Shelby to take over her accounts. If she marries him, she would not only be handing him her personal freedom, but also her hard-won career. She knows he’s not strong enough or smart enough to handle either.

The fault was mine more than Shelby’s. I had used him as women use men to complete the design of a full life, playing at love for the gratification of my vanity, wearing him as proudly as a successful prostitute wears her silver foxes to tell the world she owns a man. Going on thirty and unmarried, I had become alarmed. Pretending to love him and playing the mother game, I bought him an extravagant cigarette case, fourteen-karat gold, as a man might buy his wife an orchid or diamond to expiate infidelity.

By the end of her narrative, Laura has reached a personal breakthrough. Then she answers a ringing doorbell on a hot summer night and everything changes.

Laura is a witty and suspenseful crime novel with an outrageous twist. It’s also a profound examination of what it means to be a woman, what it means to be a man, and the sometimes fatal ways those two questions can clash.

Second Opinions

Margot Kinberg, Confessions of a Mystery Novelist (please note, review contains SPOILERS)

The character of Laura Hunt has often been thought of as a femme fatale. And on the surface, it seems that might be the case. All three of the main male characters have (or had) strong feelings for her, and she keeps herself, in her way, distant from all of them. Is she manipulating them? Is she just her own person? On the other hand, many people say she doesn’t qualify as a ‘traditional’ femme fatale. Rather, she’s an independent, empowered woman who doesn’t want to be tied to one particular man. Her character is essential to the novel, as we see how the other characters interact with her, and how they feel about her.

Pretty Sinister (please note, review contains SPOILERS)

At its core Laura is a study of the mystery of love in all its forms. Coming into play throughout all these narratives are varying viewpoints of idealized beauty (both male and female), authenticity of character, questioning gender stereotypes and ideals of manhood and femininity, and a incisive portrait of how weakness and character flaws can be the ruling emotions in the world of love.

Martin Edwards, Do You Write Under Your Own Name?

In telling her story, Caspary borrowed the narrative device favoured by Wilkie Collins – using different points of view, so as to conceal as well as reveal. It’s a device which, when employed with skill (and Caspary was highly skilled), I find engrossing.

Availability

Laura is offered as a standalone paperback and ebook from Feminist Press

It is also included in the must-have anthology Women Crime Writers: Four Suspense Novels of the 1940s published by Library of America. This anthology is available as a hardcover or ebook.

Thank you so much for the kind link. 🙂

LikeLike

Your review is wonderful! There’s so much to discuss with Laura (gender, sexuality, social class, media, etc.) and it’s all still relevant today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind words 🙂 – And you’re absolutely right about both the book and Laura’s character. It’s a rich story, and it’s not surprising that it still has power even today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely, it’s a great example of how a book can have very deep things to say while still being a fun and stylish mystery.

The movie is a total classic, maybe one of my top ten films, but it’s a shame that it somewhat overshadows the book. I put off reading this for years, thinking that I already knew the story, not realizing how much the novel expands these characters.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fine book indeed.

The movie is pretty faithful. Reading the book could *hear* Clifton Webb in every word of Lydecker. Completely opposite type physically but he caught Waldo exactly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The film is flawless. It really captures Caspary’s style. The whole cast is wonderful, with Webb as the MVP. He perfectly conveys both the comedy and tragedy of Waldo’s character. His physicality works better visually than the book’s description–having a bigger man as Waldo would not have had the right effect on film.

LikeLike